When Iceland’s Women Took a Day Off

Iceland is today known as one of the world’s most feminist countries. But the roots of this progressive title lies deep within ground-breaking moves that shook the country’s core time and again and pushed it to rethink the value of women in a nation. One such move was the Women’s Day Off—or Kvennafrídagurinn—of 1975, when 90 per cent of Icelandic women went on strike to make a point.

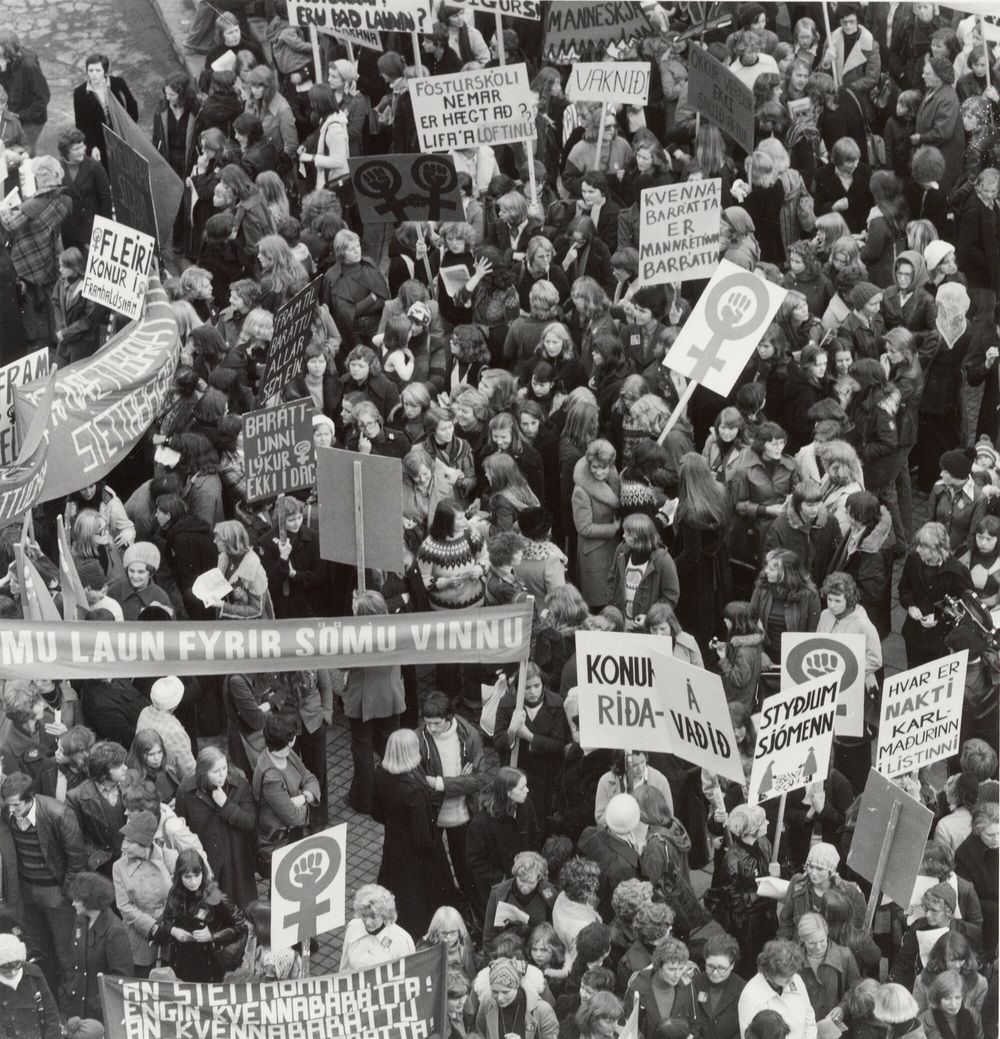

Women take a day off on 24 October 1975. Photo: kvenrettindafelag.is

It was a time of great inequality for women. For the same work, they were paid almost 60 per cent less than men. This kind of wage difference and socio-economic inequality outraged women across social and professional strata. Against this backdrop, the UN’s decision to declare 1975 an international women’s year came as a welcome opportunity to take a stand. A committee with representatives from all major feminist organisations decided to organise a commemorative event for the same. Out of these, an organisation called The Red Stockings suggested that all women go on strike to demand an equal share in the economy. But to most women, this was too radical an idea. The move could attract more harm than good—they could lose their jobs for going on strike, and also face the cold shoulder at home. It was finally agreed that the term ‘strike’ would be replaced by ‘day off’.

The jargon made all the difference. On 24 October 1975, women in Iceland stayed back home from work and did not participate in household chores or child rearing. The widespread movement was taken in good humour and garnered national and international coverage. Behind the scenes, women were still fighting a quiet battle by quitting their duty for a day. Many came forward later to share accounts of how they had to convince their bossess to take a day off, and others who themselves refused to give up their duty despite the cause resonating with their morals.

Run the World, Girls

Women take a day off on 24 October 1975. Photo: kvenrettindafelag.is

That day, fish markets shut down, for most were run by women. Even though female employees came back to finish the job by midnight, newspapers ended up printing only 16 sheets instead of the usual 24. Businesses shut down and the country came to a halt. And for the lack of women’s help, shops across the country ran out of sausages. It was only one of the many tertiary effects of the strike. Men had to take over the task of babysitting, and ended up at work with their children. The young ones had to be kept busy, so most fathers hoarded colour pencils and easy-to-make snacks for the day. Sausages, being the most popular food, ran out. That day, everyone heard noises of children playing while reporters read news on national television. There was a sense of warmth in the ripple effect—the country was realising the importance of women and taking with good humour the ill effects of their opposition.

But the aftermath of this Women’s Day Off lasted way longer than anyone had expected. Slowly but surely, the government introduced an Act for equal pay across genders by the next year. But five years later, the seeds of the movement bloomed into yet another flower of progress. In 1980, Vigdis Finnbogadottir, a divorced single mother, became the world’s first democratically elected female president by winning the elections in Iceland. This was a woman who had been a part of the 1975 strike, and owed her victory to that sultry day of radicalisation. She had been one of the 25,000 women who had assembled in downtown Reykjavik that day to sing and dance in celebration, and also to talk about what needed to be done to attain a fairer share in the world.

Vigdis Finnbogadottir. Photo: Wikimedia

Women from all walks of life participated in this subtle revolution, and a housewife, two MPs, a female worker and a representative of the womens’ organisation took the stage for speeches. The closing speech was given by Adalheidur Bjarnfredsdottir. Meanwhile, the entire nation had come to a standstill, and Vigdis was inspired to see the effect they could have in the world.

As termed by BBC, the day was a kind of baptism by fire for men. The revelations of the event hence lent it the name Long Friday. Later on, Poland held its own Black Friday to follow in Iceland’s footsteps. This protest was held against the ban on abortion.

Iceland had been one of the first countries to grant women the right to vote. Universal suffrage had come way back in 1915. Yet by 1975, only five per cent of the parliament was female. That day in October though, a spark was ignited. Everyone went back to life the next day, but with the bare understanding that women were irreplaceable and integral to society. When Vigdis ran for the seat later, she beat three men and remained unopposed for the next two terms. It was during those years that Iceland gained fame for its feministic stronghold.

Since 1975, women have taken a day off in Iceland every year. On this day they leave work a little early, increasing their time of duty commensurate with the level of progress in the country. For instance, women initially left work at 2.08pm to express the time by which they could have earned their wage if they were paid as much as men were. As wage inequalities bridged, they began to leave at 2.15pm one year, 2.25pm the next, and so on. In 2005, they were again rallying by 2.08pm against statistical suggestions that women earned 64.15 per cent less than men.

Kvennafrídagurinn, 2005. Photo: Johannes Jansson/Wikimedia

Reviewed by Your Destination

on

June 18, 2022

Rating:

Reviewed by Your Destination

on

June 18, 2022

Rating:

No comments